By: Kim Ives – Haiti Liberte

Joseph Emmanuel “Manno” Charlemagne, Haiti’s most beloved and

controversial folk singer, died in a Miami Beach hospital on Dec. 10

at the age of 69, after a struggle of several months with lung cancer

which had spread to his brain.

His rich baritone voice, trenchant lyrics, and graceful melodies

inspired the generation of Haitians which rose up against the

three-decade Duvalier dictatorship in 1986. Sometimes called the

Haitian Bob Marley or Bob Dylan, Manno’s huge popularity won him

Port-au-Prince’s mayor’s office in 1995, but his lyrical idealism soon

dashed against the rocks of Haiti’s difficult political realities, and

he was all but chased from that office. In recent years, he had

withdrawn from Haiti’s political scene, except for some ill-fated

sorties which he regretted.

Born on Apr. 14, 1948, Manno was raised mostly by his aunt in

Port-au-Prince’s Carrefour neighborhood and came of age under the

brutal dictatorship of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, who rose to power

in 1957. Both his aunt and mother were singers. His father, whose

identity Manno only learned from his mother in 1985, was also a

musician. When Manno traveled to New York to finally meet him, he

learned his father had died two months earlier.

Manno, who said he was from Haiti’s “lumpen proletariat,” started

playing guitar and singing at the age of 16, and in 1968, at age 20,

he launched a mini-djaz called Les Remarquables. But he soon moved in

the direction of the traditional twoubadou music, a form of Haitian

folk song, and launched the group Les Trouvères with singer Marco

Jeanty.

After Papa Doc died in 1971, succeeded as “President-for-Life” by his

son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, a democracy movement began to

grow in Haiti. Manno wrote politically suggestive songs about the poor

and exploited, among whom he’d grown up, and the duo began to sing at

small underground events of students and intellectuals in the late

1970s. In May 1978, the duo played their angaje (politically engaged)

songs on the airwaves of journalist Jean Dominique’s Radio Haiti

Inter, championed by deejay and station manager Richard Brisson, who

in January 1982 would be captured and killed after a failed overthrow

attempt against Duvalier.

The duo became a sensation, and later that year, musicologist Raoul

Dénis recorded their songs which were released in an album entitled

simply “Manno et Marco” by Marc Records in New York. Over the next

eight years, until Baby Doc’s overthrow on Feb. 7, 1986, the album

became the soundtrack for the pro-democracy movement both in Haiti and

its diaspora.

In 1980, the Duvalier regime stepped up its repression of democracy

activists. Manno slipped out of a concert and sought exile in the U.S.

on Jul. 4. While in Boston and New York for most of the next six

years, he became a fixture at anti-Duvalierist rallies and marches.

Along with composer Nikol Levy, he composed much of the music for

Haiti Films’ 1983 documentary Bitter Cane, which also helped propel

the anti-Duvalierist movement and Manno’s renown.

During this time, he released his first solo albums, Konviksyon (1984)

and Fini les Colonies! (1985) to worldwide acclaim.

After Duvalier’s 1986 fall, Manno returned to Haiti and became one of

the most prominent artistic and political voices of the emerging

pro-democracy lavalas movement, which brought President Jean-Bertrand

Aristide to power in February 1991. In 1990, Manno had released the

album Òganizasyon Mondyal, which cemented his fame as Haiti’s

preeminent anti-imperialist singer.

A Washington-backed coup d’état in September 1991 sent Aristide into

exile, and Haitian police arrested Manno at his home on Oct. 11. After

Hollywood stars and Amnesty International protested, he was released a

week later. Manno eventually sought refuge in Argentina’s Embassy,

where a human rights delegation, headed by former U.S. Attorney

General Ramsey Clark, met him in December 1991 (as depicted in the

1992 documentary Killing the Dream by Crowing Rooster Arts, which

played nationally in the U.S. on PBS). After the delegation raised

$3,000 for his release from the country, Manno was accorded safe

passage to the airport and flew once again into exile in January 1992.

During the next three years of his and Aristide’s exile, Manno

traveled the world playing at demonstrations, fundraisers, and

political rallies. When he returned to Haiti in 1994, he successfully

ran in 1995 for mayor of Port-au-Prince against Evans Paul, a former

ally who had indirectly supported the 1991 coup.

Once in Haiti’s third most important executive office (after President

and Prime Minister), Manno, who had just months earlier publicly

declared himself a Communist, faced many of the intractable problems

of corruption, violence, and chaos that confront any Haitian

politician. Although once allies, he ended up at odds with both

Aristide and President René Préval. When Manno’s gun-toting deputies

brutally evicted illegal vendors (mostly market women) from

Port-au-Prince’s central Champ-de-Mars square, it evoked particular

consternation among even his most loyal supporters. He finally stepped

down from the office in 1999, a few months before the end of his term.

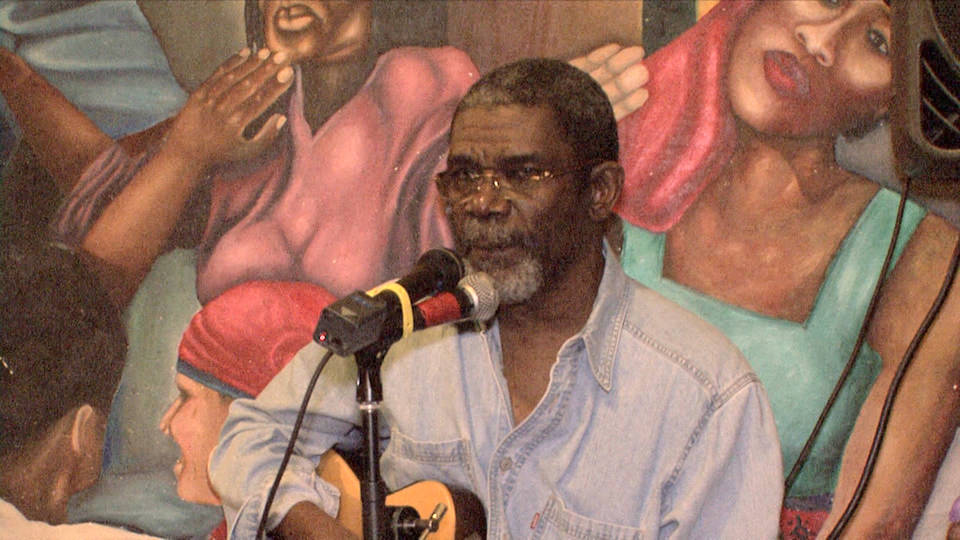

Manno moved to Miami and dropped from view for about two years, but

then in 2002, he began playing twice a week at Tap Tap Restaurant in

South Beach with Richard Laguerre (bass guitar), Damas Jean-François

(electric guitar), and Jocelyn Egourdet (tenor sax). The new band’s

music was released on CD as Manno at Tap Tap (Crowing Rooster Arts,

2004), and the band often played to a packed house over the next 15

years.

Following the 2004 coup d’état against Aristide (then serving a second

term), Manno again spoke out against the coup but also made several

provocatively critical remarks about Aristide (then exiled in South

Africa) on Haitian radio (as was his wont), which earned him the ire

of the anti-coup Lavalas masses.

Manno continued to visit Haiti, mostly to form youth chorales in

remote corners of the Haitian countryside, like Camp Perrin and

Pignon. The sting and humiliation of his political failure and his

naturally provocative style caused him to occasionally make

intemperate declarations on Haitian radios, which added to his

political marginalization.

But it was the rise of neo-Duvalierist politician Michel Martelly

which did the most damage to Manno’s reputation. Although he had been

a member of the Duvalierist paramilitary force, the Tontons Macoute,

Martelly, who also grew up in Carrefour, had known and admired Manno

as a youth. When he became Haiti’s President in 2010, Martelly courted

Manno, giving him an office and a salary as an “advisor” in the

National Palace. Citing outrageous corruption, Manno eventually quit

the job but remained on cordial terms with his “friend” and fellow

musician “Sweet Micky” Martelly, even as popular rage against the

latter grew.

Following controversial October 2015 elections, Manno agreed to serve

on an investigative commission convened by Martelly, although it was

generally viewed as a rubber-stamp body.

Following that final foray into politics, which provoked great dismay

among many, he returned to Miami, where he resumed his biweekly

performances at Tap Tap.

Last year, Manno was diagnosed with and began treatment for a fungal

lung infection, which affects many Haitians who’ve had tuberculosis.

He visited Haiti in the summer, during which time President Jovenel

Moïse’s officials tried to entice him, with money and favors, to

participate in the government’s “Caravan for Change,” a sort of

traveling political circus. Manno refused.

In late July, Manno began to have dizzy spells and speech problems.

Fearing a stroke, he quickly returned to Mt. Sinai Hospital in Miami

Beach, where doctors found a huge malignant tumor in his brain which

had mestastacized from cancer in his lungs. On Jul. 31, he underwent a

successful 10-hour operation to remove most of the tumor, but it was

followed by grueling radiation and chemotherapy sessions, which left

him weak. In early November, Manno suffered several seizures and

strokes, which sent him first back to Mt. Sinai Medical Center, and

then, briefly, the Miami Jewish Health Systems nursing home in Miami’s

Little Haiti. Just after Thanksgiving, he developed a high fever and

was rushed from the nursing home to Mt. Sinai, where they discovered

he had a pulmonary embolism. Doctors were unable to dissolve it, and

the cancer in his lungs and brain continued its inexorable march.

In his final days, surrounded by a half-sister, former wife, two sons,

a daughter, and occasional visitors from Tap Tap, Manno slipped in and

out of consciousness. When a journalist from Haïti Liberté visited his

bedside on the evening of Dec. 6, Manno suffered from tremors and had

difficulty speaking and controlling his movements, but was lucid and

humorous reminiscing about old times. “You wouldn’t understand what

we’re talking about,” he said, turning to his son, Ti Manno, who was

also in the room. “That was before you were born.”

In the final three days of his life, he was mostly unconscious, with

the hospital providing only palliative care: an oxygen mask and heavy

doses of morphine to ease his pain.

He finally died shortly after 4:00 a.m. on Sun., Dec. 10. Although

expected, the news of his death sent a shock-wave through Haitian

communities for which Manno had been a symbol of resistance to the

Duvalier dictatorship, and an authentic voice and representative of

Haitian popular culture, critical of U.S. imperialism and its misdeeds

both in Haiti and around the world.

There are several books about the musician, including Manno

Charlemagne: 30 Years of Songs published by Fondation Connaissance &

Liberté (FOKAL, 2006) , and Nicole Augereau’s graphic comic book Quand

viennent les bêtes sauvages published in 2016. Among the films about

him are Frantz Voltaire’s Konviksyon (2011) and Dans La Gueule du

Crocodile (1998) by Canadians Catherine Larivain and Lucie Ouimet.

The last album of his music, entitled Les Inédits de Manno Charlemagne

(The Unpublished Songs of Manno Charlemagne), was released in 2006.

After a private viewing for his family, there will be a public viewing

of Manno’s body on Thu., Dec. 14 at 5:30 p.m. at Notre Dame d’Haïti

Catholic Church on 62nd Street in Miami’s Little Haiti. Although Manno

was a devout atheist, there will then be a funeral mass at 7:30 p.m..

His body will be flown to Haiti on Sat., Dec. 16 and exposed on Tue.,

Dec. 19 at the Museum of the Haitian National Pantheon (MUPANAH) on

Port-au-Prince’s Champ-de-Mars. The funeral is scheduled to take place

on Fri., Dec. 22.

Meanwhile, in Brooklyn, the community group KAKOLA and Haïti Liberté

are organizing a traditional veye patriyotik (patriotic wake) to pay

homage to Manno on Fri., Dec. 15 from 7-11 p.m. at Haïti Liberté, 1583

Albany Avenue, Brooklyn, NY. At the same time in Miami, former

friends, comrades, and associates will be holding a similar tribute at

the Little Haiti Cultural Center on NE 2nd Avenue.

Although his final years were compromised by political missteps,

unseemly associations, and outbursts, Manno Charlemagne earned a

permanent place in the hearts and memories of the Haitian people for

his revolutionary, anti-imperialist, and pro-democracy songs of the

1970s, 80s, and 90s.

To give a taste of his genius and to what he dedicated his life and

art, it is fitting to close his obituary with his own words, extracted

from two classics, Fini le colonies in French, and Konviksyon in

Kreyòl;

Tu me prends tout, tu me prends tout, pour deux sous,

Toujours faudrait dire merci à genoux,

Tu m’as eu, tu m’as eu, tu m’auras plus,

C’est fini les colonies, fini le temps de mépris.

Ça va changer un jour, ça va changer bientôt, ça va changer un jour!

You take everything me, you take everything me, for two cents,

I must always say thank you on my knees,

You got me, you got me, you’ll get me more,

It’s over, the colonies, no longer the time of contempt.

It will change one day, it will change soon, it will change one day!

—-

Se konviksyon w ki pou kenbe w

Sa li ka fè w reyalize kòm malere

Tout vye chimen velekete

Se lite tout bon pou lite pou sa chanje

It’s your conviction that has to sustain you

That can allow you achieve to something as a poor person

On all the old treacherous roads

One must really struggle for things to change.

Joseph Emmanuel “Manno” Charlemagne, Haiti’s most beloved and

controversial folk singer, died in a Miami Beach hospital on Dec. 10

at the age of 69, after a struggle of several months with lung cancer

which had spread to his brain.

His rich baritone voice, trenchant lyrics, and graceful melodies

inspired the generation of Haitians which rose up against the

three-decade Duvalier dictatorship in 1986. Sometimes called the

Haitian Bob Marley or Bob Dylan, Manno’s huge popularity won him

Port-au-Prince’s mayor’s office in 1995, but his lyrical idealism soon

dashed against the rocks of Haiti’s difficult political realities, and

he was all but chased from that office. In recent years, he had

withdrawn from Haiti’s political scene, except for some ill-fated

sorties which he regretted.

Born on Apr. 14, 1948, Manno was raised mostly by his aunt in

Port-au-Prince’s Carrefour neighborhood and came of age under the

brutal dictatorship of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, who rose to power

in 1957. Both his aunt and mother were singers. His father, whose

identity Manno only learned from his mother in 1985, was also a

musician. When Manno traveled to New York to finally meet him, he

learned his father had died two months earlier.

Manno, who said he was from Haiti’s “lumpen proletariat,” started

playing guitar and singing at the age of 16, and in 1968, at age 20,

he launched a mini-djaz called Les Remarquables. But he soon moved in

the direction of the traditional twoubadou music, a form of Haitian

folk song, and launched the group Les Trouvères with singer Marco

Jeanty.

After Papa Doc died in 1971, succeeded as “President-for-Life” by his

son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, a democracy movement began to

grow in Haiti. Manno wrote politically suggestive songs about the poor

and exploited, among whom he’d grown up, and the duo began to sing at

small underground events of students and intellectuals in the late

1970s. In May 1978, the duo played their angaje (politically engaged)

songs on the airwaves of journalist Jean Dominique’s Radio Haiti

Inter, championed by deejay and station manager Richard Brisson, who

in January 1982 would be captured and killed after a failed overthrow

attempt against Duvalier.

The duo became a sensation, and later that year, musicologist Raoul

Dénis recorded their songs which were released in an album entitled

simply “Manno et Marco” by Marc Records in New York. Over the next

eight years, until Baby Doc’s overthrow on Feb. 7, 1986, the album

became the soundtrack for the pro-democracy movement both in Haiti and

its diaspora.

In 1980, the Duvalier regime stepped up its repression of democracy

activists. Manno slipped out of a concert and sought exile in the U.S.

on Jul. 4. While in Boston and New York for most of the next six

years, he became a fixture at anti-Duvalierist rallies and marches.

Along with composer Nikol Levy, he composed much of the music for

Haiti Films’ 1983 documentary Bitter Cane, which also helped propel

the anti-Duvalierist movement and Manno’s renown.

During this time, he released his first solo albums, Konviksyon (1984)

and Fini les Colonies! (1985) to worldwide acclaim.

After Duvalier’s 1986 fall, Manno returned to Haiti and became one of

the most prominent artistic and political voices of the emerging

pro-democracy lavalas movement, which brought President Jean-Bertrand

Aristide to power in February 1991. In 1990, Manno had released the

album Òganizasyon Mondyal, which cemented his fame as Haiti’s

preeminent anti-imperialist singer.

A Washington-backed coup d’état in September 1991 sent Aristide into

exile, and Haitian police arrested Manno at his home on Oct. 11. After

Hollywood stars and Amnesty International protested, he was released a

week later. Manno eventually sought refuge in Argentina’s Embassy,

where a human rights delegation, headed by former U.S. Attorney

General Ramsey Clark, met him in December 1991 (as depicted in the

1992 documentary Killing the Dream by Crowing Rooster Arts, which

played nationally in the U.S. on PBS). After the delegation raised

$3,000 for his release from the country, Manno was accorded safe

passage to the airport and flew once again into exile in January 1992.

During the next three years of his and Aristide’s exile, Manno

traveled the world playing at demonstrations, fundraisers, and

political rallies. When he returned to Haiti in 1994, he successfully

ran in 1995 for mayor of Port-au-Prince against Evans Paul, a former

ally who had indirectly supported the 1991 coup.

Once in Haiti’s third most important executive office (after President

and Prime Minister), Manno, who had just months earlier publicly

declared himself a Communist, faced many of the intractable problems

of corruption, violence, and chaos that confront any Haitian

politician. Although once allies, he ended up at odds with both

Aristide and President René Préval. When Manno’s gun-toting deputies

brutally evicted illegal vendors (mostly market women) from

Port-au-Prince’s central Champ-de-Mars square, it evoked particular

consternation among even his most loyal supporters. He finally stepped

down from the office in 1999, a few months before the end of his term.

Manno moved to Miami and dropped from view for about two years, but

then in 2002, he began playing twice a week at Tap Tap Restaurant in

South Beach with Richard Laguerre (bass guitar), Damas Jean-François

(electric guitar), and Jocelyn Egourdet (tenor sax). The new band’s

music was released on CD as Manno at Tap Tap (Crowing Rooster Arts,

2004), and the band often played to a packed house over the next 15

years.

Following the 2004 coup d’état against Aristide (then serving a second

term), Manno again spoke out against the coup but also made several

provocatively critical remarks about Aristide (then exiled in South

Africa) on Haitian radio (as was his wont), which earned him the ire

of the anti-coup Lavalas masses.

Manno continued to visit Haiti, mostly to form youth chorales in

remote corners of the Haitian countryside, like Camp Perrin and

Pignon. The sting and humiliation of his political failure and his

naturally provocative style caused him to occasionally make

intemperate declarations on Haitian radios, which added to his

political marginalization.

But it was the rise of neo-Duvalierist politician Michel Martelly

which did the most damage to Manno’s reputation. Although he had been

a member of the Duvalierist paramilitary force, the Tontons Macoute,

Martelly, who also grew up in Carrefour, had known and admired Manno

as a youth. When he became Haiti’s President in 2010, Martelly courted

Manno, giving him an office and a salary as an “advisor” in the

National Palace. Citing outrageous corruption, Manno eventually quit

the job but remained on cordial terms with his “friend” and fellow

musician “Sweet Micky” Martelly, even as popular rage against the

latter grew.

Following controversial October 2015 elections, Manno agreed to serve

on an investigative commission convened by Martelly, although it was

generally viewed as a rubber-stamp body.

Following that final foray into politics, which provoked great dismay

among many, he returned to Miami, where he resumed his biweekly

performances at Tap Tap.

Last year, Manno was diagnosed with and began treatment for a fungal

lung infection, which affects many Haitians who’ve had tuberculosis.

He visited Haiti in the summer, during which time President Jovenel

Moïse’s officials tried to entice him, with money and favors, to

participate in the government’s “Caravan for Change,” a sort of

traveling political circus. Manno refused.

In late July, Manno began to have dizzy spells and speech problems.

Fearing a stroke, he quickly returned to Mt. Sinai Hospital in Miami

Beach, where doctors found a huge malignant tumor in his brain which

had mestastacized from cancer in his lungs. On Jul. 31, he underwent a

successful 10-hour operation to remove most of the tumor, but it was

followed by grueling radiation and chemotherapy sessions, which left

him weak. In early November, Manno suffered several seizures and

strokes, which sent him first back to Mt. Sinai Medical Center, and

then, briefly, the Miami Jewish Health Systems nursing home in Miami’s

Little Haiti. Just after Thanksgiving, he developed a high fever and

was rushed from the nursing home to Mt. Sinai, where they discovered

he had a pulmonary embolism. Doctors were unable to dissolve it, and

the cancer in his lungs and brain continued its inexorable march.

In his final days, surrounded by a half-sister, former wife, two sons,

a daughter, and occasional visitors from Tap Tap, Manno slipped in and

out of consciousness. When a journalist from Haïti Liberté visited his

bedside on the evening of Dec. 6, Manno suffered from tremors and had

difficulty speaking and controlling his movements, but was lucid and

humorous reminiscing about old times. “You wouldn’t understand what

we’re talking about,” he said, turning to his son, Ti Manno, who was

also in the room. “That was before you were born.”

In the final three days of his life, he was mostly unconscious, with

the hospital providing only palliative care: an oxygen mask and heavy

doses of morphine to ease his pain.

He finally died shortly after 4:00 a.m. on Sun., Dec. 10. Although

expected, the news of his death sent a shock-wave through Haitian

communities for which Manno had been a symbol of resistance to the

Duvalier dictatorship, and an authentic voice and representative of

Haitian popular culture, critical of U.S. imperialism and its misdeeds

both in Haiti and around the world.

There are several books about the musician, including Manno

Charlemagne: 30 Years of Songs published by Fondation Connaissance &

Liberté (FOKAL, 2006) , and Nicole Augereau’s graphic comic book Quand

viennent les bêtes sauvages published in 2016. Among the films about

him are Frantz Voltaire’s Konviksyon (2011) and Dans La Gueule du

Crocodile (1998) by Canadians Catherine Larivain and Lucie Ouimet.

The last album of his music, entitled Les Inédits de Manno Charlemagne

(The Unpublished Songs of Manno Charlemagne), was released in 2006.

After a private viewing for his family, there will be a public viewing

of Manno’s body on Thu., Dec. 14 at 5:30 p.m. at Notre Dame d’Haïti

Catholic Church on 62nd Street in Miami’s Little Haiti. Although Manno

was a devout atheist, there will then be a funeral mass at 7:30 p.m..

His body will be flown to Haiti on Sat., Dec. 16 and exposed on Tue.,

Dec. 19 at the Museum of the Haitian National Pantheon (MUPANAH) on

Port-au-Prince’s Champ-de-Mars. The funeral is scheduled to take place

on Fri., Dec. 22.

Meanwhile, in Brooklyn, the community group KAKOLA and Haïti Liberté

are organizing a traditional veye patriyotik (patriotic wake) to pay

homage to Manno on Fri., Dec. 15 from 7-11 p.m. at Haïti Liberté, 1583

Albany Avenue, Brooklyn, NY. At the same time in Miami, former

friends, comrades, and associates will be holding a similar tribute at

the Little Haiti Cultural Center on NE 2nd Avenue.

Although his final years were compromised by political missteps,

unseemly associations, and outbursts, Manno Charlemagne earned a

permanent place in the hearts and memories of the Haitian people for

his revolutionary, anti-imperialist, and pro-democracy songs of the

1970s, 80s, and 90s.

To give a taste of his genius and to what he dedicated his life and

art, it is fitting to close his obituary with his own words, extracted

from two classics, Fini le colonies in French, and Konviksyon in

Kreyòl;

Tu me prends tout, tu me prends tout, pour deux sous,

Toujours faudrait dire merci à genoux,

Tu m’as eu, tu m’as eu, tu m’auras plus,

C’est fini les colonies, fini le temps de mépris.

Ça va changer un jour, ça va changer bientôt, ça va changer un jour!

You take everything me, you take everything me, for two cents,

I must always say thank you on my knees,

You got me, you got me, you’ll get me more,

It’s over, the colonies, no longer the time of contempt.

It will change one day, it will change soon, it will change one day!

—-

Se konviksyon w ki pou kenbe w

Sa li ka fè w reyalize kòm malere

Tout vye chimen velekete

Se lite tout bon pou lite pou sa chanje

It’s your conviction that has to sustain you

That can allow you achieve to something as a poor person

On all the old treacherous roads

One must really struggle for things to change.